The Year of the Rabbit began on January 22nd 2023, replacing the Year of the Tiger. This means that shops, homes and the Taipei Lantern Festival were all decked out in rabbits ranging from sweet and funny to gigantic and demonic. As someone who had grown up in Europe, it definitely made me feel like Easter had come early this year.

Whereas tigers, who were still represented in surprisingly large numbers at the Lantern Festival, feature most prominently as man- (and woman-)eaters in Chinese literature, rabbits also make plenty of appearances: as the Jade Rabbit 玉兔 who lives on the moon and grinds medicinal herbs with its mortar and pestle; the unfortunate hare that broke its neck on a tree stump and led that dude from Song make a fool of himself (兔 or 兔子 translates to both rabbit and hare); and not least are the colony of white rabbits that are a sign of the protagonists’ love in The Untamed 陳情令 (2019).

But today I want to talk about another story involving rabbits: King Wen’s Three Rabbits 文王三兔子 from Fengshen yanyi 封神演義. Though the rabbits only appear at the very end, this story has it all: political drama, supernatural birth, cannibalism, a test of prophetic ability, a daring escape, sexual harassment, heart break, filial piety, and finally: a pun.

The dramatis personae: King Zhou 紂王: last king of the Shang 商 dynasty, a tyrant Su Daji 蘇妲己: his consort, secretly a fox spirit Ji Chang 姬昌: Earl of the West 西伯侯, the future King Wen 文王 of the Zhou 周 dynasty Boyikao 伯邑考: King Wen's eldest son Leizhenzi 雷震子: a thunder god, King Wen's adopted hundredth son Yunzhong zi 雲中子: Leizhenzi's Daoist master various ministers and generals

The story begins when Ji Chang 姬昌 is summoned to the capital, where he predicts he will be imprisoned for seven years. He entreats his family and the ministers of his earldom not to follow him there, trusting that fate will set him free after seven years. On route to the capital, he passes a woman’s tomb, when thunder splits the sky and it is discovered that the corps has given birth to a baby. Ji Chang adopts this boy as his 100th son, names him Leizhenzi 雷震子 (Master Thunderclap/ Son of Thunderclap) and immediately hands him over to the Daoist Yunzhong zi 雲中子 (Master Within the Clouds) who accepts the child as his disciple and takes him away into the mountains. Continuing on his journey, Ji Chang arrives at the capital where after some intrigue against all four Earls, the Earl of the South and East are executed, while the sycophantic Earl of the North is pardoned and Ji Chang is banished to Youli 羑里, a settlement close to the capital Zhaoge 朝歌 and far from the Ji Chang’s earldom in Xiqi 西岐. Part of the reason why Ji Chang is banished here, is the threat he poses to King Zhou’s 紂王 rule through his gift of soothsaying 演數/ 演先天數.

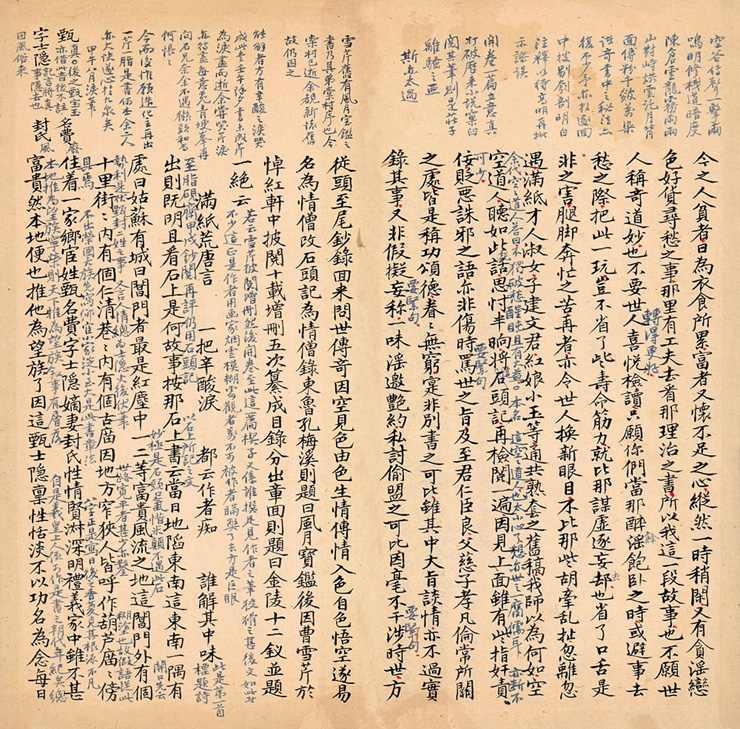

Right side: Ji Chang finding Leizhenzi (Chapter 10); Left side: Ji Chang soothsaying in Youli (Chapter 11).

After seven year had passed with Ji Chang in house arrest in Youli, his oldest son Boyikao 伯邑考 became impatient and, as a good filial son, decided to set out to the capital to petition King Zhou for his father’s release. His earnest and filial entreaty, coupled with his pleasing skill on the zither 琴 initially almost led to success in persuading the king. Yet after Boyikao fights of favorite royal consort (and secret fox spirit) Su Daji’s 蘇妲己 sexual harassment during a zither lesson, she in turn accuses him of having made advances towards her. Enraged, King Zhou has Boyikao executed. Faced with Boyikao’s dead body, Daji is struck by inspiration: this would be a good opportunity to put Ji Chang’s soothsaying abilities to the test. Why not bake the flesh of his oldest son into a pie and send it to Ji Chang as a special boon from his sovereign? Should he eat it, he clearly knows nothing about fate and can be safely let go. If he refuses to eat the pie, he obviously known that it contains the flesh of his son and can be dealt with accordingly.

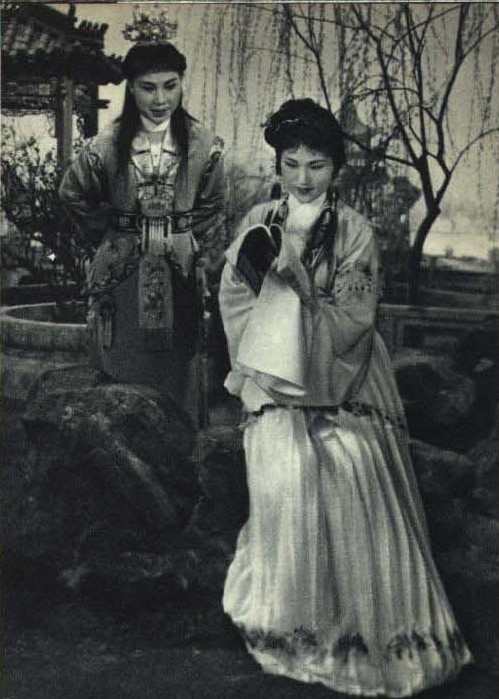

Boyikao playing the zither for King Zhou and Su Daji (Chapter 19)

Yet Ji Chang’s abilities go beyond this simple dialectic: he knows that if he does not eat his own son, he will never return to his earldom in Xiqi. Heartbroken, he comes to the conclusion that eating the pie is the only viable option. When word reaches King Zhou that Ji Chang has indeed eaten his own son, he is delighted that his strongest rival “failed” this test of ability and releases him from his house arrest, yet changes his mind soon after Ji Chang begins his journey home. Having only passed one of five mountain passes on his way home, Ji Chang is beset by fierce generals in hot pursuit. But who should come to his rescue but his 100th son, Leizhenzi? The boy has grown up in the past seven years, and, thanks to his master Yunzhongzi, grown a pair of wings and the frightening stature of a thunder god. He fights off his father’s pursuers and safely flies Ji Chang across the remaining mountain passes to the outskirts of Xiqi, before returning to his master in the mountains.

Right: Ji Chang receiving the pies (Chapter 20); Left: Leizhenzi saving his father (Chapter 21).

Here, Ji Chang, returning home alone without entourage, horse or luggage, is finally overcome by grief. Doubling over he vomits (tu 吐) his son’s (zi 子) flesh, whereupon three rabbits (tuzi 兔子) hop away through the grass. (I told you there would be an amazing pun!!!)

Ji Chang vomiting a rabbit (Chapter 22).

The story of how King Zhou feed Boyikao to his own father King Wen goes back all the way to antiquity and, according to Meulenbeld’s research, can be read alongside a whole host of both voluntary and involuntary (filial) cannibalism. The rabbits are a newer edition and only appear in stories from the Yuan dynasty onward. As to why Boyikao’s flesh turns into three rabbits (besides the awesome pun of course), I have no idea. But certainly, it makes for better theatre to have King Wen pull rabbits out of his cloak than the alternative. (Around the 70 mins mark in this recording of 八百八年, Boyikao appears earlier in the play, while Leizhenzi only appears after the rabbits in this version.)

___________________________

For more on ancient Chinese (filial) cannibalism, see:

Meulenbeld, Mark RE. Demonic Warfare: Daoism, Territorial Networks, and the History of a Ming Novel. University of Hawaii Press, 2015.